Mould Resistant Housing – Lessons from the North

Controlling mould in the home can sometimes be challenging. Trevor Trainor, Building Science Specialist, explains how his research projects monitor building walls, roofs, and foundation systems in the north to prevent mould from growing and spreading, describing how mould is a living organism and that it is vital for our ecosystem, and how it affects our homes and our health. Building designers and constructors ensure that the conditions of the building will prevent mould growth and spreading. Further explaining how moisture is in our homes and how they try to disrupt the cycle of mould growth and spreading before the mould exposure can affect the building or our health. The lessons in this article help us understand the buildings' structure and how moisture, insulation, humidity, and other elements contribute to the home's mould.

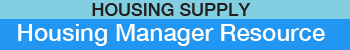

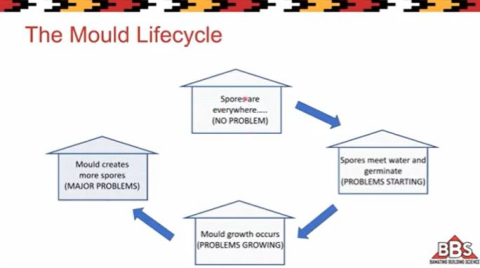

Mould is everywhere. In our homes, outside in our environment. You can have mould spores; they only grow once in the right conditions. Building designers and constructors are to ensure those conditions don't occur. For mould to grow, it requires food, oxygen, heat, and water. We build our buildings with mould food, wood products, and paper-based products like drywall.

We try to disrupt the mould lifestyle to avoid mould problems in our homes. Uncontrolled mould growth can cause poor indoor air quality, resulting in respiratory issues and skin infections, especially in children.

Lesson 1:

Energy efficiency only matters if we control the moisture in our buildings. We need to control the humidity before we worry about energy-efficient buildings. We need to control liquid water, rain, snow, and groundwater, and we also need to control water vapour and the water molecules contained in the air in our buildings.

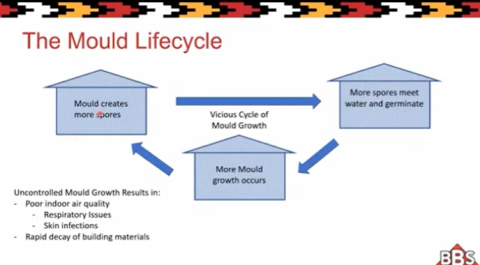

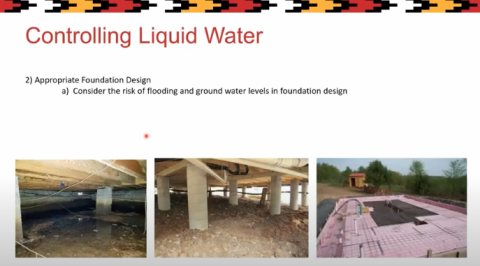

Controlling liquid water with appropriate roof designs by using overhangs to reduce the amount of rain that reaches the wall system—using eavestroughing, flashings, and downspouts to move water away from the building. For the most appropriate foundation design of a building, you must consider the risk of flooding and groundwater levels. Several design processes can separate the building from the ground's moisture. Having the appropriate grading around the building, proper drop, and flow away from the building so rainwater won't collect around the foundation.

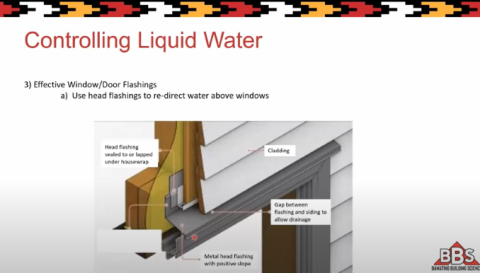

Concrete and pressure-treated wood can have moisture moving inside the materials. Having window and door flashings can re-direct water.

There are two types of windows. Windows that leak and windows that will leak. We manage that leak with sill pan flashings. 2 critical parts of the windows are flashing at the head, and the sill flashing. These must go in before the window, or the window won't be properly sealed. You also need to ensure a drainage path to the outside.

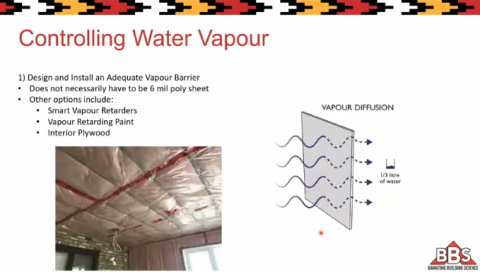

It's crucial to have water vapour barriers in the building's walls, roof, and insulated parts. Vapour control is easy, and the vapour barrier and air vapour functions have different requirements. The vapour barrier must be there, but the Air Vapor Barrier must be excellent. Vapour diffusion can allow a third of a litre of water into your walls.

Lesson 2:

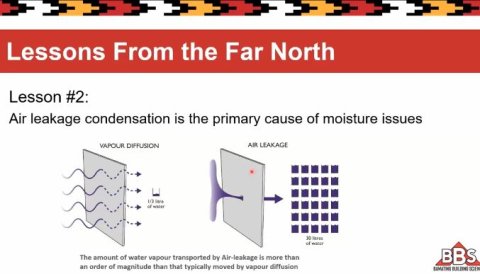

Air Leakage can allow up to 30 litres of water into the walls. Stopping airflow is much more critical and challenging to do. Air Leakage condensation is the primary cause of moisture and mould issues—the more significant the amount of air leakage, the more tremendous condensation. Having a lot of people in the house causes more condensation. The colder the climate, the more significant the amount of condensation. To minimize air leakage, we need to reduce condensation. The higher the humidity in the building, the more walls will have condensation.

How does airflow into a wall create moisture problems? Condensation. If there is any air leakage from the house and it gets into the wall system, it will meet the cold and deposit moisture in the wall.

Lesson 3:

Building air tightness is the best defence against air leakage condensation. Design and install an excellent air barrier to reduce air leakage condensation.

Air Barrier:

- It could be on the interior or exterior of the building.

- Must be continuous and effective at stopping airflows.

- It does not necessarily have to be a 6mil poly sheet.

- Other options include.

- Exterior house wrap.

- Exterior rigid insulation.

- Exterior taped sheathing.

- 2 lb spray foam insulation.

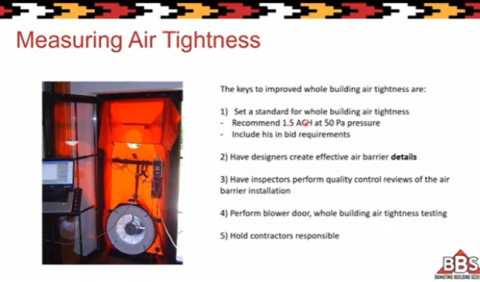

Whichever seal you use must be completely sealed for air tightness at the transition from the walls to the roof, walls to foundations and windows and doors, and other penetrations. The only way to know if you have achieved good air tightness is by measuring air tightness.

The designer can help the builder detail those to ensure it is done correctly. A whole building air tightness testing is commonly known as a 'Blower Door Test.' Trevor Trainor is pushing this process as key in the far north because we must start testing every new building for air tightness. Eventually, this cost will be dramatically overwhelmed by the savings for these buildings' durability, air quality, and lack of mould.

There are two keys to improving the whole building's air tightness. The community must set a standard for the builders and designers for the entire building's airtightness.

The building code says, "There shall be a continuous barrier to air movement." There needs to be specifics as to how good those must be. We must go above code and require an actual measured valve of 1.5 air changes per hour.

We should perform Blower Doors Tests 100% on new buildings and hold contractors responsible for meeting those goals. Before handing the keys over, we must know that the building is airtight.

Lesson 4:

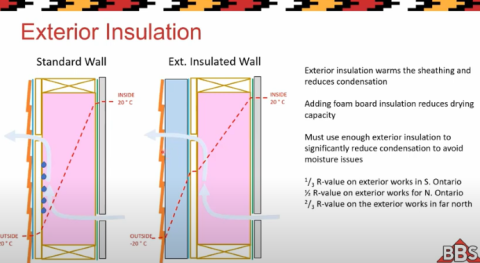

Exterior insulation is an effective defence against Air Leakage Condensation.

The temperature profile changes when you add a significant amount of exterior insulation outside of the sheathing, and adding external insulation warms the sheathing and reduces condensation. You need to add enough exterior insulation because if you use foam board insulation, we are reducing the ability of this system to dry.

Another strategy to reduce air leakage condensation is to add exterior insulation. We started to do that with roofs and walls in the far North, which works well.

Lesson 5:

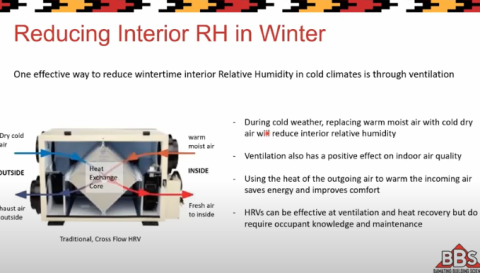

Reducing interior Relative Humidity reduces air leakage condensation—specifically the internal relative humidity during the winter. Overcrowding in a home can lead to high moisture levels, which results in high interior relative humidity levels. Higher relative humidity during cold temperatures leads to more significant air leakage condensation. We deal with relative moisture through ventilation. When we bring cold outdoor air inside and warm it up with our heating systems or an HRV (Heating Recovery Ventilator), we replace high-humidity air or low-moisture air coming inside.

The Heat Recovery Ventilator helps us control the humidity inside the building and helps save energy. The HRV is taking some heat from the outgoing air and bringing it to the incoming air, so we are not bringing in colder air. We are helping to reduce the interior relative humidity by bringing in dry air from the outside and replacing the warm air inside with dry air from the outside.

HRVs (Heating Recovery Ventilators) can be highly effective at ventilation and require maintenance. There is a new type of HRV, and it is called the Reverse Flow HRV. They can be more expensive, but they are more efficient. This technology has been used commercially and will be made for residential applications. We need better building design and construction in the far North, resulting in higher upfront costs but lower overall.

Questions and Answers:

Is there much difference or distinction between what is happening or the building and what you would do further North vs. Southern Ontario?

All the concepts discussed are relevant to all the climate zones in Canada but what we see in the far North is that the flaws in design and construction become very much immediate issues. Instead of seeing a condensation issue in 5 or 10 years in northern Ontario, we see them in 1 or 2 years in the far North. The moisture and mould accumulation rate are much faster in the North. The far North is an excellent place to start, and if we can solve the problems there, we know the exact solutions will work for the South. Some specific climate design issues would affect the different climate zones differently.

Is there a case study regarding traditional lumber vs. log-style homes in terms of addressing mould, especially with the cost of materials today?

There probably are some studies out there. We do understand the science of something like a log wall vs. an insulated stud wall and how they differ from each other, and the positives and negatives of each. Certainly, a monolithic wall, like a log wall or a triple-wide brick wall, is not as susceptible to mould growth and condensation. They are not as energy-efficient and uncomfortable to live in. There are pluses and minuses to both. From a moisture durability standpoint, a monolithic wall structure like logs, stones, or bricks will be less susceptible to condensation and mould growth. It would also be expensive to build.

2-part question. In conjunction with the vapour barrier in the house, the cost of doing the pressure test within the house, do you know how much exactly that is? Secondly, because the houses are already built and a lot of first nation communities have a lot of mould issues. Are there tests that can be after the fact that it is already built, to find out what the pressure is? We want to control the mould in the house, to reduce that humidity in the house, how small of a dehumidifier can we use to be effective?

It is not the right approach to use a dehumidifier. The right approach is to improve the air tightness in the building and improve the ventilation. The Blower Door Kit, the fan, the red shroud, and all the pieces that come with it, the thing that measures pressure. The cost to buy one cost about $7000. You can really improve the air tightness of an existing building by doing a negative pressure test and finding where the big leaks are and fixing them.

How would we do the negative pressure test?

The fan itself goes into the doorway, and it moves enough air in or out to either pressurize or depressurize the house. If it is cold out, it puts negative pressure on your building and it sucks frigid air in at all the little spots where the air leakage is and you can go around and feel them with your hands if you do not have a fancy thermal camera, you will have to do some destructive openings in drywall or trim to get to those spots. Certainly, they can be fixed in existing buildings by identifying them first.

We are all aware that First Nations do not have a building code to abide by. What would your recommendations be? At what point can we develop a strategy that individuals, Tribal Councils, and First Nations can adopt to prevent this, how can we get recommendations that Chief and Councils and First Nations can adopt and support right down to the community members?

That is a great question and one I have been pondering for a long time. One concept I have been working on is an Indigenous Building Certification Program, which means things above the code. I consider the code the bare minimum that you can do, and the code itself does not always address some of the important things that we are worried about in Indigenous housing. So, my concept is that every building must meet the building code, whether it is national or Ontario. It should also be certified as a Certified Indigenous housing program. I have been trying to get some momentum for this idea and get some government funding. We need to go beyond code, and we need our own code or an addendum to the code to solve these problems. I am glad you mentioned that because it is a tricky question and it is something that needs some attention, but I have not figured out the best way to do that yet.

Regarding the R-value, what are your thoughts on what is a realistic value that makes a comfortable home vs. the minimum?

It is so climate specific. We need to place the insulation properly to avoid moisture problems. You can get away with low insulation levels if they are continuous; you will use more energy to heat that home. So, from an energy and financial perspective, it makes sense to have higher insulation levels. We must consider higher R Values and thicker and more effective wall and roof systems.

By: Tricia Cook, Content Navigator